Description

PERIPHERAL NERVE SURGERY FOR PIRIFORMIS SYNDROME

Piriformis syndrome is to the leg what neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is to the arm. Piriformis syndrome is a severely under-diagnosed problem occurring when the nerve roots of L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3, which make up part of the lumbosacral plexus, become compressed between the bony inferior rim of the greater sciatic notch of the pelvis and the overlying piriformis muscle as they converge to form the proximal sciatic nerve. The greater sciatic notch is effectively a window from the inside of the pelvis to the outside of the pelvis. The structures traveling through this relatively tight space include both the piriformis muscle and the 5 nerve roots that make up the sciatic nerve.

Any type of injury mechanism involving blunt trauma to the buttocks, forceful flexing of the hip joint or significant traction to the leg can lead to piriformis syndrome. This can happen during slip and fall injuries, car accidents, surgeries to replace the hip or knee, or crush injuries to the pelvis, to name just a few. Often, the injury occurs to the piriformis itself leading to swelling, bleeding, and scarring of the tissue around the lumbosacral plexus/proximal sciatic nerve. This can lead to the piriformis muscle applying pressure to the lumbosacral plexus/proximal sciatic nerve, as well as scarring or tethering of the nerves that prevents the nerves from being able to glide against surrounding tissue with the motion of the body.

Similar to neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, piriformis syndrome can produce a whole array of clinical symptoms and therefore can mimic other common spine or orthopedic conditions which involve the low back, pelvis, hips, and legs. Patients can often undergo unnecessary spine surgery or orthopedic procedures, including total hip replacement surgery for the symptoms associated with an unrecognized piriformis syndrome.

Piriformis syndrome can present as anything from isolated pain in the deep buttock to pain that radiates all the way from the low back down into the foot and anything in between. Most commonly, the symptoms of piriformis syndrome are characterized as “sciatica” with pain in the buttock that radiates down into the posterior thigh, usually no lower than the back of the knee. Patients with piriformis syndrome commonly complain that sitting significantly increases their pain level. Two patients with the same underlying problem, piriformis syndrome, can present with very different clinical pictures. Diagnosing piriformis syndrome accurately requires a careful patient history as well as a detailed lower extremity peripheral nerve examination. Once again, EMG/NCV studies and currently available imaging technology is usually unable to correctly identify cases of piriformis syndrome. MRI imaging of the lumbar spine, however, is critical in order to rule spinal pathology as the primary or contributing source of the symptoms.

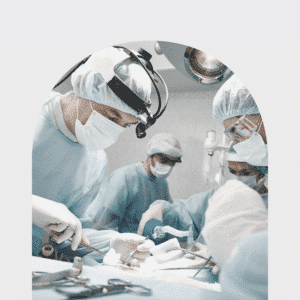

Treatment for piriformis syndrome depends on the severity and duration of the symptoms. Mild or acute cases may resolve with physical therapy, steroid injections targeting the piriformis muscle, and medication. For more severe cases or in instances where the symptoms have been present for a long time, surgical decompression is the only real way for the patient to experience excellent, lasting relief from the pain. Surgery involves removal of as much of the piriformis muscle as possible as well as removing any scar tissue or other structures that might be pressing on the lumbosacral plexus/proximal sciatic nerve in the deep posterior buttock area. As with the removal of the scalene muscles to treat neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, there are several redundant muscles in the deep posterior pelvis that act synergistically with the piriformis muscle. Therefore, removal of the piriformis muscle does not result in any discernible clinical deficit in terms of the ability to move the affected leg. The surgery is surprisingly easy for the patient in terms of post-op course and recovery time. Piriformis surgery is done in an outpatient setting. The patient is immediately weight-bearing on the operated side and there is usually only mild to moderate pain related to the surgery itself postoperatively. The pain from surgery typically lasts from a few days to no more than about 1-2 weeks for most patients. Patients typically have very good early relief from the original pain and are able to return to a normal activity or exercise routine within 4 weeks from the date of surgery.